Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

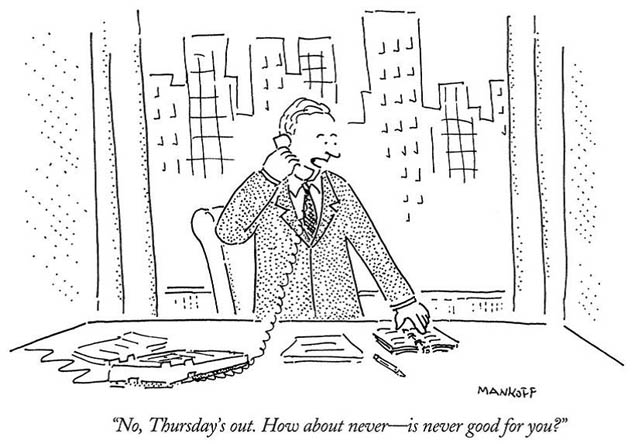

One of New Yorker Cartoon Editor Bob Mankoff's famous cartoons, "How About Never?"

The New Yorker may be known for great long-form journalism, but the magazine’s tone is set by its whimsical cartoons and illustrations poking fun at the serious, the topical, and the timeless. Longtime cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s new memoir is a journey through a life spent on the serious business of being funny, along the way introducing us to the quirky personalities behind favorite cartoons.

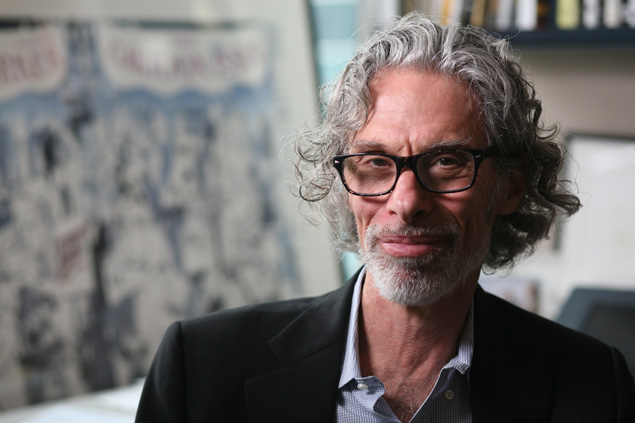

Bob Mankoff. Credit: Davina Pardo

First Cartoon, “The Point of View,” first appeared in the British magazine Punch in 1899.

Cartoons Featured in Bob Mankoff’s New Memoir

MR. KOJO NNAMDI...for great long-form journalism, but for many the magazine is distinctive for something else, its sense of humor. That lighter side is expressed through cartoons and illustrations that poke fun at, well, just about everything, whether social morals or the news or modern life. Long-time cartoon editor Bob Mankoff's new memoir is a rub through nearly four decades spent on the serious business of being funny.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIAlong the way he introduces us to the cast of quirky characters behind some of our favorite cartoons. And he joins us to discuss all of this. As I mentioned, Bob Mankoff is the cartoon editor of the New Yorker magazine. He's the author of "How About Never-Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartooning." Bob Mankoff, thank you so much for joining us.

MR. BOB MANKOFFIt's a real pleasure. I feel like I'm always here.

NNAMDIYou are indeed.

MANKOFFI did. I've been doing a lot of radio shows and actually they're great because everybody always has some different slants on humor, the New Yorker cartoons and questions they're going to ask me.

NNAMDIPlus nobody's going to ask you about your pocket handkerchief when you're on the radio. That's what happens when you go on television. Why a memoir? Why now?

MANKOFFWell, we both shared maybe the information just recently that, you know, get to be the Biblical three-square -- I'm -- soon I'll be pushing 70 from the wrong side.

NNAMDISame here.

MANKOFFYou know what I mean? And 70 may be the new 50 but that isn't the new alive. Okay. So I figured, you know, that maybe joke -- I figured well, you know what? I had a sort of interesting experience, people are interested in the New Yorker and I wanted to meld those together, you know, to tell my story and really the story in the New Yorker Magazine. Which for the last four decades have been intersecting.

NNAMDIYou have been, as you pointed out, the cartoon editor of the New York editor for more than two decades. You've been associated with it for the last four decades or so. Your most famous cartoon is also the title of this book. It features a man standing at his desk, looking at his calendar. He's saying, no, earth is out. How about never? Does never work for you? That (technical) becoming a catch phrase and aphorism in short a classic. Can you talk about that cartoon and where the idea for it came from?

MANKOFFWell, you got it slightly wrong. It's how about never is never good for you. Not it's….

NNAMDIIs never good for you, thank you.

MANKOFF...it'll work, but you know, I'm a little picky on those things. But, well, really the idea, I got it in 1993. One of the things I talk about in this book is if you only get one idea for a cartoon, you're not a cartoonist. Cartoonists get 10 or 15 ideas and they do it every week. And that's what I was doing. So that was sort of the last one that I threw on what's called my batch of cartoons. I didn't think much of it. It came out of a personal experience where I was trying to make an appointment with someone and they were putting me off. And I just said, that's not (technical) I guess at the last part, how about never. Is never good for you? Yep, that was the guide.

MANKOFFSo I really reversed it for the cartoon. I think it works for people because humor's about conflict. It's about the -- well, some of it is anyway. It's about the conflict of the way we know the world is supposed to be properly in a way we would like the world to be if we had our druthers. So that cartoon, the conflict there is between rudeness and politeness. The message goes right through. It's polite, the syntax no, Thursday's out. How about never? Is never good for you? That's why you need that little tag end.

MANKOFFSo it's resonated with people because it's something that they identify, something they wish they could say and they don't say it so they have it on their refrigerator or their bulletin board or they license it from the cartoon.

NNAMDIThat makes it a classic recipe for humor?

MANKOFFYes. A classic recipe for humor is everything that's bad looked at in some other light. There are no cartoons about good marriages, good vacations, good anything really. Nothing -- you know, that's for greeting cards. But humor is a way of us coping with the fact that we're a species that both have to cooperate and compete. There's always a tension.

NNAMDIYou can join this conversation. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Do you enjoy cartoons, New Yorker cartoons, political cartoons, the funny pages or other comics? Have you ever entered the New Yorker's cartoon caption contest, 800-433-8850. Or you can send email to kojo@wamu.org. Our guest is Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor of the New Yorker magazine and author of the book "How About Never-Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartooning."

NNAMDIYou make it look easy but getting a cartoon published in the New Yorker wasn't and still isn't easy. What was your path getting to that first cartoon in the magazine?

MANKOFFIt was -- it was the (word?) , to say the least, because I did many other things. I'm -- you know, during the '60s I worked for the Welfare Department. I taught speed reading to Catholic girls by telling them that if they didn't read faster they'd burn in hell. I did all sorts of things. I had gone to the high school in music and art from 1958 to 1962. I had some modest talent for drawing.

MANKOFFAs a kid, I was funny. You know, I talk about my background, being a Jewish kid growing up in the '50s and the early '60s and that, you know, at that time many of the models for humor, even if the public at large didn't know, they were -- I knew they were Jewish. So many Jewish comedians. You know, George Burns and Jack Benny and Milton Berle were all Jewish. And even as late as 1980, 80 percent of the people in comedy were Jewish.

MANKOFFSo I had that background and I think there is something -- I mean, I think all minorities share humor as a type of coping. I think for the Jewish people it was especially acute because of the background they came out of where you had this incredible conflict. The conflict was the Jews are the chosen people. And the Jews kept asking themselves, God, would you please choose somebody else because you have this huge paradox. We were chosen yet we're persecuted and people want to destroy us. And so the Jews use humor to cope.

MANKOFFSo that was sort of my background. You know, I do say that growing up. And now Jewish humor and humor is absolutely prevalent throughout society. It's a (word?) for everyone, but it wasn't always the case. It was not always the case. And Jewish humor and Jews in comedy are very important to American humor. And the truth is, Jews are to American humor what blacks for to American basketball. It's the unique circumstances where the environment, culture, everything led to it.

MANKOFFSo that was my background. I was a funny kid. I imitated Jerry Lewis. I got attention in class by being the class clown or the class satirist…

NNAMDIYou even looked like Jerry Lewis when you were a kid. I saw the pictures.

MANKOFFI looked like -- I definitely did. I definitely did. I definitely did. So finally after I -- I had to tell the story in the book about how I was a graduate student and sort of failed at that. I was on the cusp of my PhD but the cusp was so big it stretched forever. That I naturally -- when I became 30 and became a cartoonist -- or tried to become a cartoonist, took me 2,000 cartoons to get published in the New Yorker. I was published in many other magazines. I sort of hit it off right away, you know, that way.

NNAMDIWell, I found it fascinating that very early on you made a calculation that if you could sell a certain number of cartoons to the New Yorker per year that you would be able to live on that for the entire year. But it took you about, oh, 15, 20 years to get there.

MANKOFFIt took me 15, 20 years and that's why my parents Lou and Molly Mankoff, a generous report from the Lou and Molly Mankoff Foundation over the years, you know, they certainly didn't want me to not become a psychologist and become a cartoonist. Absolutely not. You know, my father was born in 1908. And when I told him, hey, you know, I want to be a cartoonist for the New Yorker he said, you know they already have people who do that. You know, like it was closed. I said, well, yes, one of them might die and then I'll just be there.

MANKOFFSo, as I said, the path was (word?) and before graduate school, I tell the story in the book how I was the -- a terrible student. I was trying to avoid the Vietnam War. So my father was an ad 'cause I was going to go to Canada for $300. We'll get you into graduate school. We paid the $300, I got the call. And they said, oh we got you into graduate school. I don't know if this is a program for you. This is 1967. It's Atlanta University and you're the only white student.

MANKOFFSo I went to Atlanta University, the only white student, for six months.

NNAMDIThe height of the black power.

MANKOFFThe height of the black power, which is so -- everybody -- people used to -- guys used to come up to me and of course they thought I was somehow part of the movement.

NNAMDISaid the only reason this white guy is at this black school is he's obviously a part of the movement.

MANKOFFThe only obvious reason -- or the FBI. Okay. So my roommate was a guy from Ghana who you're listening (unintelligible) and he was a radical, as I've heard you were. And he would say to me -- and I'll do this bad accent -- they should burn the country down. Burn it down. Burn -- so he ranted and -- we were good friends but he would go into these rants. And I said fine and he was very nice. He never tried to set me on fire.

MANKOFFBut then he became the attorney -- the assistant attorney general of Kentucky. I recently heard from him, whereas I say in the book I think he's strictly enforced the laws against arson.

NNAMDIThat's right. Apparently he marched from being a radical to being...

MANKOFFI think you know all about that.

NNAMDI...to being part of the mainstream establishment. You have a distinctive style. And that distinctive style is in itself a hallmark of New Yorker artists. Your cartoons are instantly recognizable. Can you describe how you make your cartoons and how you developed that style?

MANKOFFOkay. I don't know if you can hear -- I do it with dots. Like I'm doing this right next to...

NNAMDII saw that.

MANKOFF...I'm doing it right next to the microphone now. You hear that's how fast it's going. And the dots for me are like a type of sketching where I sort of like create a face and create a body and do that. It's a weird style. I don't...

NNAMDIIt's takes forever.

MANKOFFIt takes forever. It takes forever -- well, not forever. A couple hours now. And -- but I liked it because I'm an antsy guy. The Yiddish word is I have no (unintelligible) Yiddish for sitting flesh. So I -- so this thing keeps me at the drawing board like working, working. And so much of humor comes from shifting between the unconscious and the conscious. The ideas come to you and it's very good actually to be doing something that's distracting in a way. It's very hard to just get a joke or make a joke by saying, okay think of a joke. Think of something funny. But if you know you have to think of funny and you do something else, I think that it comes around.

NNAMDI800-433-8850 is our number. Our guest is Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor of the New Yorker magazine, author of "How About Never-Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons (sic) ." 800-433-8850. If you pick up a New Yorker, do you, like many of us do, read the cartoons first? Tell us why. Or if you don't, why not? 800-433-8850. You discovered the power of humor one day. I want you to tell the story about what happened in a sociology class in college. How it may have influenced the path you took later.

MANKOFFWell, like I said, I wasn't a good student and I went to Syracuse University in the '60s. This was before Atlanta University. And at that time you could go to these, you know, large lecture classes. And you didn't even have to go to them. No one kept the attendance. Well, if no one was keeping attendance, I wasn't there. So I went to the first class just to find out what the syllabus was, got the textbook and everything.

MANKOFFThen I went to the last class, and the last class was the exam. So it's a big lecture hall and I'm late. And I'm totally, you know, hippy-ish looking, very, very long hair. I come in, everyone's scribbling in their blue books. I sit down and naturally getting the attention of the teacher. And the teacher comes over to me, he looms over me and he says, who the hell are you? So I wait a beat and I look up at him and say, you know, I could very well ask you the same question.

MANKOFFAnd so the tables get turned. Everybody laughs, even he laughs.

NNAMDIHe didn't smack you or kick you out of the class.

MANKOFFNo, no, he didn't. You know, it was just this thing saying that in this whole structure of the world, even of which a lever that you could push that could temporarily turn the tables, it was something that could shift power around. And, you know, it's very, very useful for that. Now for the most part, the people who use power are people who are already powerful. And if you've ever been with a boss -- the boss it's easy to get laughs. But you don't necessarily have to be the boss if you're a lot funnier than the boss, to at least temporarily be the boss.

NNAMDIThe New Yorker is the gold standard for captioned cartoons, but the captioned cartoon has a history. Can you talk about how it evolved?

MANKOFFYeah, I can. I talk about this in the book. Cartoon -- the word cartoon is a rather old word and it comes really from the Italian and it comes from renaissance painting. All it really meant was a sketch, an under drawing. An under drawing that then would later become a painting. In Punch magazine, which is a humor magazine from the 1840s, maybe even to maybe 20 years ago -- it's now unfortunately defunct -- but it started in the 1840s.

MANKOFF1840s parliament burns down in this very, very rich neighborhood. And there's a big -- I mean, actually the neighborhood's surrounded by poverty, and there's a contest for cartoons for paintings which will now hang in parliament. And so Punch starts to parody these. It creates its own cartoons it thinks are appropriate, mocking the contradiction between the opulence and the poverty.

MANKOFFOver time they create cartoon number one, cartoon number two. Eventually it becomes to be known as a humorous parody as in illustration. And by the 1880s and 1890s, you have what we now call a cartoon -- as I show in the book, the cartoons are very, very much drawn out. What the New Yorker does is it compresses the cartoons so you have this incongruous picture like a James Thurber drawing in which there's two swordsmen. One has knocked the other guy's head off and the caption is, touche.

MANKOFFAnd if you looked at the history of cartooning you would see -- what you would see -- you would see the long process where the New Yorker helps cartooning become free in terms of its drawings file and in terms of (unintelligible) vernacular.

NNAMDIYou can go to our website kojoshow.org to see many of the cartoons that you can find in the New Yorker or in the book "How About Never-Is Never Good for You?" by Bob Mankoff. We have an amusing sample that you can find there also in the book of a Punch magazine cartoon from 1899, the lady in the fancy hat at a performance. And the old gentleman behind her saying, I paid ten shillings to see this performance and your hat -- she interrupts him saying, sir, I paid ten guineas for this hat and I want to be seen. What did the New Yorker bring to cartoons when it launched?

MANKOFFWell, when it launched it almost brought nothing. In 1925 the cartoons were very, very much like everybody else's cartoons, very stagy. Not quite as stagy as that Punch cartoon. But Harold Ross who was the great original editor and he had been in the army, an editor of Stars and Stripes, he knew he wanted something new and fresh and original.

MANKOFFAnd what the New Yorker eventually came was this idea of a single caption which worked perfectly with the drawing and sort of explained that incongruous drawing. So you have the great Peter Arno cartoon from the late '30s in which a plane is crashing in the background. And the test pilot is parachuting out. Everyone, all the emergency personnel are running towards the plane concerned. The engineer of the plane is walking away. We see his face and he's saying, well back to the old drawing board.

MANKOFFAnd that's really where that phrase comes into the language. So the New Yorker -- that's what the New Yorker really cartooned in. And then what it eventually did for the New Yorker -- for the cartoon itself was that it made the idea of having a sense of humor within a serious publication palatable, where previously, for the most part, comedy and comics have been insulated, as they are now in newspapers. You have the comic section.

MANKOFFBut through the New Yorker the cartoons were right there with all the serious stuff as well. It showed you that that's what it meant to be part of a really well-rounded human being, to have this type of sense of humor that you could go from being absolutely serious to being seriously funny or even just silly.

NNAMDIAnd of course going back to the drawing board or going back to the old drawing board, has entered a language and stayed there in much the same way as is never good for you. When a cartoonist -- and you talk about the craft of cartooning and what goes into it and how many ideas you throw around before you get into it, and you land on is never good for you. And that becomes your identifying mark virtually for the rest of your life.

MANKOFFEven afterwards.

NNAMDIEven afterwards.

MANKOFFI know what's going to be -- it's going to be in my obituary.

NNAMDIEven afterwards. Do you have any idea at the time when you land on that that it's going to have that lasting effect?

MANKOFFNo, none. I mean, the -- when you start...

NNAMDIEither that or you think everyone is going to have a lasting effect.

MANKOFFNo. When you start out you think -- you know what everyone's going to like. That's sort of the naivety of youth. You think, I can't believe this is so great. And if you're in any profession, you know, like all the -- like the shows you do. And some of them will strike your chord and some of them won't and whatever, and you'll get a tremendous response. Maybe you have an intuition but often you'll be surprised. And you have to -- that's one of the things that when you're in a craft or an art, that's also -- it's not just art for art's sake.

MANKOFFYou're not -- I'm not doing these cartoons just for the sake of cartoons and you're not doing this radio show just for the sake of, hey this is my art form. It's got to connect with someone but you never know exactly how it's going to connect. And it's surprising. I think that's one of the mysteries and wonderful things about it.

NNAMDIOn to the telephones now. We will start with Carol Anne in Bethesda, Md. Carol Anne, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

CAROL ANNEHi, Kojo. How are you?

NNAMDII am well.

ANNEMr. Mankoff, I grew up in Brooklyn. I did not go to the High School of Arts -- music and art. But I went to New Utrecht. And I graduated with David Geffen who...

NNAMDIOh.

ANNE...I think was -- we used to have these thing called (word?) which I thought brought out some of the greatest humor. And these were, like, competitive shows between the juniors and the seniors and the sophomores.

MANKOFFYeah.

ANNEAnd these were all the kids that couldn't get into music and art, I guess, or didn't know they should go. But, anyway, just thought you'd get a kick out of that. And the only reason I read The New Yorker is the cartoons.

MANKOFFWell, you're making a mistake.

MANKOFFI mean, it's -- you know, it happens to be -- I never believe that when people say that. Really? You're spending your -- you should just go up to the cartoon bank then and down -- look at the cartoons (unintelligible).

NNAMDIWe'll talk about the cartoon bank later in this show.

MANKOFFYeah. Yeah. But I'm sure. So go -- you know what I mean. I think, just as a proper thing, you should at least -- I'm going to report you if you don't read at least one article. Okay?

ANNEAll right. I'm going to (unintelligible)...

NNAMDIBut, Carol Anne, in some respects, you're one of those people who -- I'm one who goes to the cartoons first. We eventually get to the articles. But we go to the cartoons first. And, in fact, one of the reasons is I always want to see how many of the cartoons I'm going to get because I don't remember one issue of the magazine in which I got all of the cartoons. Do you get them all?

ANNEI have the same experience.

NNAMDIAh, (unintelligible).

MANKOFFThat's good. That's what -- that's exactly -- you know, there's a rumor that we always put in a few that no one can get. But that's not true. It's just that the range of humor and the subjectivity of humor -- and what The New Yorker is, is it gives us a chance. We can play around. If you saw the first cartoon that Roz Chast did, or even the old James Thurber cartoons, they are cartoons that everybody gets, absolutely. It's a dog, and he's dressed in a suit. And he's at a bar. And the bartender says, Scotch and toilet water? Everybody gets that.

NNAMDIYes.

MANKOFFEverybody understands that. And then there are cartoons that are just a -- just crazy, like cartoons -- so it's like enjoying a Rodney Dangerfield joke or enjoying Monty Python.

NNAMDIYeah. Yeah.

MANKOFFSo humor, like music, like literature, like everything, is different. And when you apply the same thing where, oh, I got to put these all things together, rather than just enjoy it, that's when you get to the, I don't get it.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. Our guest is Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor for The New Yorker magazine, and the author of "How About Never? Is Never Good For You? My Life in Cartoons." If you'd like to call, the number is 800-433-8850. Shoot us an email to kojo@wamu.org. Or send us a tweet, @kojoshow. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIOur guest is Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor of The New Yorker magazine and author of "How About Never? Is Never Good For You? My Life in Cartoons." Bob, so many people want to talk to you that I'm going to have to swallow most of my questions. But this one I'm going to ask 'cause you mentioned it earlier.

MANKOFFAll right.

NNAMDIYou've been pretty entrepreneurial in your work. In 1990, you founded the Cartoon Bank. Tell us about that.

MANKOFFCartoon Bank, you know, I was a cartoonist for The New Yorker. The New Yorker had rejected my cartoons, rejected most cartoons. I talked to my fellow cartoonists, and I said, hey, these cartoons aren't too bad. How about we create a database or a repository for all the cartoons that were rejected? I did that in the early 1990s. I thought those were all going to go on CDs. This was before the Internet. It intersected perfectly with the Internet. In 1997, The New Yorker bought it from me. And that's how come you have the complete cartoons in The New Yorker because then I went back.

MANKOFFAnd we archived all the cartoons that ever appeared at The New Yorker. You can go up and get a print, or you can license them for your PowerPoint, your textbooks, thousands of them all the time. I mean, I made a lot more cartoons -- I made a lot more money on "How About Never? Is Never Good For You?" That put my daughter through college by licensing that cartoon than I ever did for selling it. So go license it. The cartoonists need the money.

NNAMDIDid you have the first Macintosh computer ever created?

MANKOFFI bought the one -- Mac fans. I bought the one, you know, from that commercial where, like, the blonde Olympic gal is running towards the Orwellian 1984 figure. And so I bought the first Mc in 1984 where it had 128K of memory, where, if you're a computer nerd, you know Word -- or was Mac Word, I think, was 50K. MacPaint was 50K. You know, the whole thing -- and I bought it at Radio Shack. So I was in graduate school. I had done some programming and stuff. And then I just did have this idea, right from the very beginning, that this stuff could store cartoons.

NNAMDIAnd thus the Cartoon Bank was started. There have been laments from people who miss those they consider to be the classic New Yorker cartoonists of yesteryear.

MANKOFFYeah.

NNAMDIWhat's your response to those folks?

MANKOFFWell, you know, the humor changes, just like music. So there are people missing the classic songs or the '40s and '50s. You don't really have to miss them, and you don't have to miss them. You can go look at all those cartoons. They're up there now. But just as though, hey, Frank Sinatra's absolutely great.

MANKOFFNewton Crosby, absolutely wonderful. But if you turn on the radio now, that's not what people are going to be listening to. Humor changes also. Got to change with the times. You say you miss the classic cartoons of the '40s or the '50s. And you know what? If those people from the 1890s, from those punch cartoons, were alive, they'd be missing those cartoons.

NNAMDIThat's true.

MANKOFFBut -- and I -- but I revere all of it. But I also -- one of the things I talk about in the book is that humor has to be fed by youth -- has to be fed by youth, or else it becomes a museum. And so the cartoon, the humor, a lot of it is more absurd because our world is more absurd. Our world is stranger. Our world is a -- you know, so much of humor is just now a mashup. Well, you know what, our world is a mashup.

MANKOFFWe live where tragedy and comedy are cheek by jowl. I mean, they're right next to each other. If you watch Brian Williams on the news and you watch how it is, here's this terrible story. And then as long as you have a little intermediate story that's not too bad, then you can have a humorous story. And that's the whole spectrum. I think the only way people deal with this incredible conflict in our minds is through humor. And the humor is stranger and weirder.

NNAMDIOn to the telephones again. Here is Gail in Burke, Va. Gail, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

GAILYes. Hi, Kojo. I want to say that I subscribe to The New Yorker, and have for years. I was an English major in college, and I got it then. And I used to think I looked pretty darn cool carrying The New Yorker around. But I'm calling about the cartoon caption contest that's always in the back of the magazine. Do you choose those winners? I've actually -- my husband and I have actually submitted some captions that we thought were actually really funny and probably would win. And we didn't. So I'm wondering, how do you go about choosing that? How many (unintelligible) ?

MANKOFFI'm going to tell you.

NNAMDIYou don't know the half of it. Ask him about Roger Ebert. But go ahead.

MANKOFFYeah. (unintelligible) This is how they're chosen. Five to 10,000 come in every week. I've written computer programs because it's got 5- to 10,000 different entries. Okay? Whatever your entry was was a lot like other people's entries. Almost always, that's almost always the case. So you get a comic landscape of maybe 60 or 70 different takes on it.

MANKOFFFrom that, we create sort of categories, lists of, you know, what we think is the best from each of those different categories. So, you know, there's the turtle now. And the turtle, between his shell and his body, he has all stuff. He has books, and he has papers. And he has everything. So we'll take -- some of them will be about tax time. Some of them will be about working from home.

MANKOFFSome of them will be about playing off of turtle tropes. Then I take those. I take about seven or -- I get about 10 of those. I use SurveyMonkey. SurveyMonkey's a survey tool. I send it out to -- we look at every single one. I send it out to about 40 or 50 editors of The New Yorker. They rate them. I pick three. They go up online. So, you know, definitely, yours may have been funnier. But I think we give it an absolute real hero shot that has integrity.

NNAMDIWell, Gail, here's a tip for you. In this book, "How About Never? Is Never Good For You?," he promises in one chapter to teach people how to win the caption contest.

MANKOFFWin is in quotes.

NNAMDIYes. Yes, and so it does.

MANKOFFBut I give you hints about how to go about it. And one thing is you get better at things that you do a lot. I don't know how many times you've entered. Like I said, Roger Ebert entered 108. You should generate multiple captions from the one that you select. You should try those captions out on your friends. And you should keep trying it. And you...

NNAMDIWhy do you think so many of us want to tap in to our inner humorist?

MANKOFFI think it's because the idea of having a sense of humor has been transformed over time, that it's not -- you simply must do more than appreciate humor. You've got to be able to be more than just tell jokes or retell humor. You yourself have to be humorous, which means you have to be able to create it in some way, maybe not for the captioning contest. But in some way, you understand that being funny or having a sense of humor is a way that we communicate with each other. And I think that's really why it's most -- so popular.

NNAMDIOn to Gary. Gail, thank you for your call. Now, Gary in Bethesda, Md. Hi, Gary.

GARYEasy for you to say.

GARYHey, I'm a tech kind of guy, and I've always appreciated the humor in the cartoons from not only The New Yorker but elsewhere.

MANKOFFSure.

GARYThat's sort of our -- a lead into say this is a topic that people know about. I think, of course, of the -- on the Internet, no one knows you're a dog cartoon. But a lot of others way back to the era of videotape recorders and all that.

MANKOFFOh, yeah, sure.

GARYIt wasn't popular until The New Yorker commented on it, and then everybody knew about it.

MANKOFFWell, that's sort of how it works. It could be techs. It's could be Higgs boson. It could be string theory. It's got to reach that -- now, interesting, you know, on the Internet, you know, that cartoon was done in 1993. It was sort of a little bit before everyone sort of knew, you know, really what the Internet was.

MANKOFFAnd so when it's blogs or Facebook, I mean, you know, when blogs started to become big, there's one dog saying to another, I used to blog a lot, but now I just go back to barking incessantly. The -- so there's something about The New Yorker, I think, that is a little bit ambiguous but gets at the heart of it. And so it could be tech. It could be social issues, like same-sex marriage where there's a couple and a guy looking at a TV and the guy saying, gays and lesbians getting married, haven't they suffered enough?

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call. As editor, one of your jobs has been to develop the next generation of cartoonists, but what about diversity in cartooning? First, there are not very many female cartoonists. Can you talk a little bit about the reasons for that?

MANKOFFWell, that's really something that we're committed to. There actually are more, Roz Chast, and Emily Flake, and Liza Donnelly, and there certainly are female cartoonists. To some extent, it's how culture, you know, has pushed more men into comedy in general than women. I think that's changing, changing radically, but to some extent, you know, when I tell a story in my book, being funny is akin to misbehaving. You know what I mean?

NNAMDIYes.

MANKOFFYou know, the kid who's -- the thing -- me saying that at the time I did in that class with that teacher, I don't think at that time -- maybe now that's something that a girl or a female would have said. That's something that -- so boys are given a wider leeway to misbehave. And humor, just interrupting, changing the narrative, saying something that maybe that's transgressive, maybe something that's off color, maybe something that's nasty, which a lot of humor can be, I think -- so there's a lot more men in that. That's changing. And, you know, we're having more women cartoonists all the time.

NNAMDIWhat about other kinds of diversity? I've got to say I don't know if I recall ever seeing a person of color in a New Yorker cartoon.

MANKOFFWell, there are -- no. Bill Haefeli draws people of color, but he draws them so subtly that you don't actually -- you know, if you actually look at the people, they're people of color. But, you know, you have to do that where you're subservient to the joke. You know, if you have a black guy and a white guy and they're talking to each other, just because of the way our culture is, people will start to think, this is going to be a...

NNAMDIThis is going to be about race.

MANKOFFThis is going to be about race. So you could -- it's like I say, if I start a joke and I say, okay, so an imam, a priest, and a rabbi walk into a bar -- oh, this is not about religion.

MANKOFFYou know, it's going to be something about religion. But The New Yorker is open. One of the things is, as I say in this book, there's very so few people who do this to start. So in terms of diversity, I would love to have more black cartoonists, more Hispanic cartoonists, more -- everyone really contributing to it. But the truth is very few people actually do it, and it's a very hard way to make a living.

NNAMDIHere is Hanora in Arlington, Va. Hanora, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

HANORAHi. I grew up in the New York metropolitan area, to be oblique about it, and I also did some cartooning in college. Well, I am loving the show today, so thank you very much. I'm a huge, huge fan of The New Yorker, was brought up on it, and not just the cartoons.

MANKOFFRight.

HANORAI read the articles, too. But I wanted to ask -- I've always wanted to ask this. And I can't believe I have the opportunity to ask that (unintelligible)...

MANKOFFI'm getting excited myself. Just can't wait, what this is going to be.

HANORAThe infamous cover of the Obamas -- and you know the one I'm talking about.

MANKOFFHave no idea.

HANORAWith the -- yeah, okay. I always wanted to ask, was that deliberately drawn to incite all kinds of argument and discussion and, you know, outrage (unintelligible) ?

MANKOFFWell, first of all, I don't...

NNAMDI(unintelligible).

MANKOFFI don't do the covers (unintelligible). I think it was originally drawn, 'cause I know Barry Blitt who did it, to make a point. And the point was a satirical point that the -- which, you know, most people who read The New Yorker knew, which was these were these maligned lies and fiction that -- and the original sketches of the cover did have, like, O'Reilly and Rush Limbaugh sort of outside sort of to cue it.

MANKOFFBut that -- what Barry thought, and I have talked to him about this, was that this was so over the top that no one could actually think that The New Yorker believed this. And they were satirizing it. And so it was a joke that I think people got. But then people misconstrued. It's almost like people became -- you know, people can be offended by something just because it shows the topic, rather than trying to understand what the joke -- what was the joke? It wouldn't make any sense for the joke -- for The New Yorker to believe this. So, anyway, that's my defense of that cover.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call, Hanora. And I'm afraid we're just about out of time. Bob Mankoff is the cartoon editor of The New Yorker magazine and the author of the book "How About Never? Is Never Good For You? My Life in Cartoons." Bob Mankoff, thank you so much for joining us.

MANKOFFBeen my pleasure.

NNAMDIAnd good luck on the book. Thank you all for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.